FROM A LAND OF NO MAN...

Autobiographical reflections by Kanjo Také

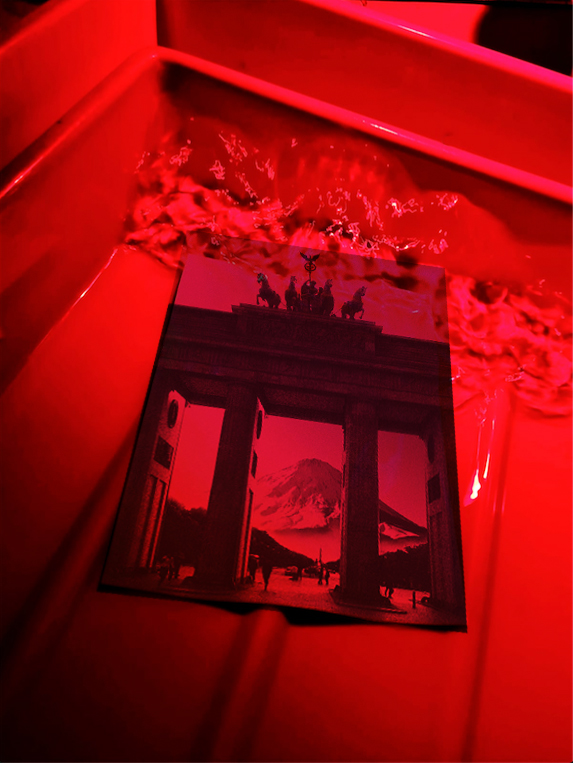

The developer tray

READ MORE

When I was seven years old, I stood in an older friend’s photo laboratory and gazed in fascination: under the red lighting, a landscape magically appeared on the paper in the developing dish. Making pictures has enthralled me ever since. It became a passion to make pictures in any and every form, regardless of whether they were sketched, painted or photographed. It was always all the same for me. I would consider which technique would best make the picture’s idea visible.

01/19

Skywalker

READ MORE

From earliest childhood, I’ve never been particularly interested in material things. I was bored by wish lists for Santa Claus. Immediately after Christmas, I would give away whatever gifts I’d received. What interested me was the immaterial, the spiritual, the sound of a musical instrument, the whistling of the wind, dream worlds, fragrances, the rustling of the sea, reflections in the water, cloud formations: these were the things toward which I turned my attention so that, by the process of free association, pictures would appear to me.

02/19

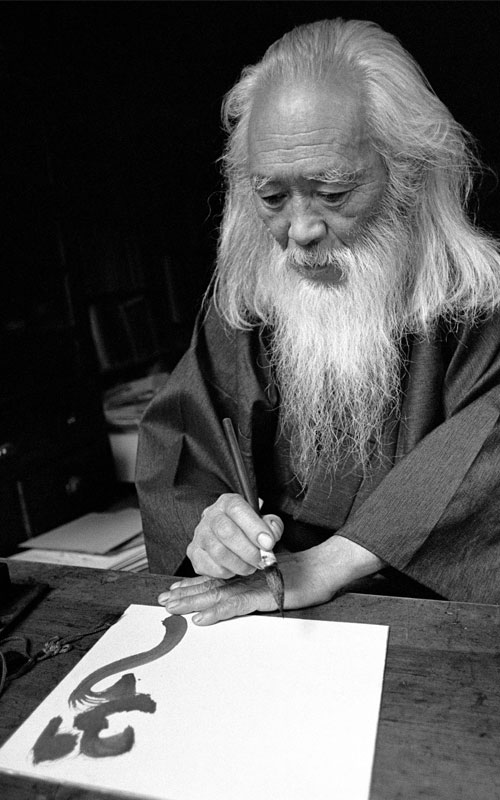

Monk

READ MORE

At age thirteen, I had a very earnest talk with a friend of the same age. The son of a family of German diplomats, he had just returned from New Delhi to Berlin. Franz did some Indian fakir’s tricks for me. He even thrust a needle through his right cheek without the slightest grimace. He told me that the Indians don’t believe in what they see, but in what we in the West regard as fanciful imagination. That may have influenced me, or perhaps it even formatively shaped me and my worldview. This attitude was strengthened by reading the words of wise people from Asia and Europe, who urged us not to allow material things to torture us and not to covet them. For a long time, I was pursued by the idea of entering a monastery and studying only what interested me.

03/19

Ryoanji

READ MORE

In order to live my own life, at age 27 I separated myself from my father’s expectations and opted to forego, as his only child, an inheritance of more than 500 million dollars. Later I visited his urn in the famous Ryoanji rock garden in Kyoto. A monk placed my father’s urn on the Shinto altar for “a discussion” with me and explained that my father’s name – Goichi Takeuchi – had been changed for his afterlife. On the one side is his mundane name, Takeuchi, which means “the interior of bamboo,” i.e. the void from which all of us come. A new name was given to him for the Beyond. Shintoists generally shelter their deceased parents and ancestors in little shrines in their homes: they speak with them regularly and symbolically give them fresh food. In front of my father’s urn, reconciliation with him occurred for me. The temple of his final resting place is situated beside the resting place of a deceased Japanese tenno. In return for this resting place for his journey into eternity, my father had bequeathed his entire fortune to the Shinto temple.

04/19

The invisible

READ MORE

During my visit to the famous rock garden at Ryoanji, I learned about the garden’s creation in the fifteenth century. To encourage his disciples’ enlightenment, a Zen Buddhist monk built a stone garden with fifteen stones. Variously sized stones are arranged in five groups atop white gravel spreadover on an area measuring ca. thirty meters in length and ten meters in width. But regardless of which corner he chooses as his vantage point, a viewer can see only fourteen stones. It is said that the fifteenth stone becomes visible only through single-minded concentration and profound Zen meditation. While I was meditating in the garden, I suddenly understood that all fifteen stones are visible only from a bird’s eye view, i.e. gravitation blocks our view of the fifteenth stone. I believe that the invisible becomes visible only through the imagination. For me, this also means the creation of art.

05/19

Yume

READ MORE

On a visit to the parents of my Japanese friend Kunito Nagaoka in Nagano in the Japanese Alps, they showed me a Zen temple where Kunito had learned how to concentrate. He told me that as a child, he had been totally unable to concentrate and that his parents, in their helplessness, had sent him to the temple. Kunito personally experienced concentration directly through the concentration of the highest-ranking priest at the temple. Today Kunito is a professor at the Kyoto Art Academy. This made it clear to me that something which had previously been nearly impossible can only be achieved through the high quality of a living example.

In the same temple garden, I discovered a monk making music. He was sitting on a piece of corrugated cardboard beside the river, playing melodies of his own composition on reeds and blades of grass. During our encounter, he asked me where I came from. I told him I come from Germany. He answered with a smile and by playing Mozart’s “Eine kleine Nachtmusik” on a slender reed stretched between his right and left thumbs. For me, this was the diametrical opposite of academia and the antipole to a role model. Gifted with perfect pitch, he could easily interpret classical European music.

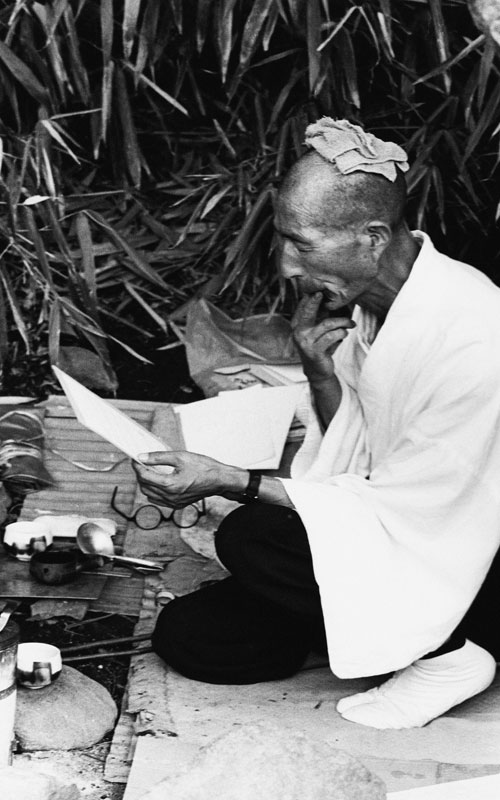

06/19

Grass flute players

READ MORE

On a visit to the parents of my Japanese friend Kunito Nagaoka in Nagano in the Japanese Alps, they showed me a Zen temple where Kunito had learned how to concentrate. He told me that as a child, he had been totally unable to concentrate and that his parents, in their helplessness, had sent him to the temple. Kunito personally experienced concentration directly through the concentration of the highest-ranking priest at the temple. Today Kunito is a professor at the Kyoto Art Academy. This made it clear to me that something which had previously been nearly impossible can only be achieved through the high quality of a living example.

In the same temple garden, I discovered a monk making music. He was sitting on a piece of corrugated cardboard beside the river, playing melodies of his own composition on reeds and blades of grass. During our encounter, he asked me where I came from. I told him I come from Germany. He answered with a smile and by playing Mozart’s “Eine kleine Nachtmusik” on a slender reed stretched between his right and left thumbs. For me, this was the diametrical opposite of academia and the antipole to a role model. Gifted with perfect pitch, he could easily interpret classical European music.

07/19

Aunt Tetsu

READ MORE

After my father’s death, I traveled once again to his northern Japanese homeland in Obihiro, Hokkaido. Aunt Tetsu Masahisa, his older sister, had a rainbow trout farm there. She made available to me one of her many pickup trucks for an extended journey around Hokkaido. My cousin Hasuro accompanied me on my wintry excursion, as did temperatures ranging from minus ten to minus thirty-five degrees Celsius. We drove past crater lakes and arrived at the frozen Siberian Sea. Beside the lakes, I saw totem-like wooden poles: they had been made by Ainus, the indigenous people of Hokkaido, and they reminded me of North American Indian totem poles. Passing the prison camp for dangerous criminals at Wakanai in the northernmost part of Japan, we drove onto an infinitely large white plain. After a long drive through no-man’s-land, Hasuro asked me if it wouldn’t be a good idea to turn around because we’d been driving for several hours on the frozen northern ocean that leads to the Sakhalin Islands, which belong to Russia. On our way back, we drove near the coast and saw a dead forest: the lower halves of the trees were immersed in the ice-covered sea, and their upper halves extended above the frozen surface. They were backlit by the setting sun, which floated like a red fireball above the horizon, dematerializing the icy plain into a glaring golden-red field of light, from which filigreed, black, Giacometti-like figures danced weightlessly. I thought, “This is surreal, like a dream or a vision.” But it was the absolute reality. Hasuro and I saw it with our own eyes.

08/19

Koi

READ MORE

After my father’s death, I traveled once again to his northern Japanese homeland in Obihiro, Hokkaido. Aunt Tetsu Masahisa, his older sister, had a rainbow trout farm there. She made available to me one of her many pickup trucks for an extended journey around Hokkaido. My cousin Hasuro accompanied me on my wintry excursion, as did temperatures ranging from minus ten to minus thirty-five degrees Celsius. We drove past crater lakes and arrived at the frozen Siberian Sea. Beside the lakes, I saw totem-like wooden poles: they had been made by Ainus, the indigenous people of Hokkaido, and they reminded me of North American Indian totem poles. Passing the prison camp for dangerous criminals at Wakanai in the northernmost part of Japan, we drove onto an infinitely large white plain. After a long drive through no-man’s-land, Hasuro asked me if it wouldn’t be a good idea to turn around because we’d been driving for several hours on the frozen northern ocean that leads to the Sakhalin Islands, which belong to Russia. On our way back, we drove near the coast and saw a dead forest: the lower halves of the trees were immersed in the ice-covered sea, and their upper halves extended above the frozen surface. They were backlit by the setting sun, which floated like a red fireball above the horizon, dematerializing the icy plain into a glaring golden-red field of light, from which filigreed, black, Giacometti-like figures danced weightlessly. I thought, “This is surreal, like a dream or a vision.” But it was the absolute reality. Hasuro and I saw it with our own eyes.

09/19

Rainbow

READ MORE

When I visited my Aunt Tetsu on “Boys’ Day,” I saw a school of colorful fish swimming across the clear blue sky. Colored textile fishes were affixed to hundreds of tall flagpoles – equally as many fishes as there were boys in each family. The fishes hung alongside the flagpoles when the wind was still; but when a breeze came up, the shapes of the smaller and larger fishes would become visible as they swam through white clouds. I learned the symbolism behind this holiday: “Only after you become big and strong enough and can swim against the current, only then will you be seen.”

On one of my visits to Kyoto, I became acquainted with the enthusiasm the Japanese feel for subtle indirectness. In the private home of a noble shogun, I entered a classical tatami room and saw a rainbow that had been painted across the corner and across two walls at right angles to each other. The spectral colors shone on the walls, but where an arc of red should have been, there was nothing to see except a neutral white surface. When I asked if he was planning to have the artwork restored, he answered “no, it is exactly as its artist intended it.” When the piece was being created, the artist and the shogun’s gardener had agreed that a maple tree would be planted in the garden and pruned so that on sunny autumn days, its red leaves would reflect light onto the white surface in the rainbow painting. This would produce perfection. The underlying realization is that the ideal situation, i.e. consummate perfection, exists only for a short time in life.

10/19

Tabla

READ MORE

My journey to Japan began in Kerala, in South India, where I became familiar with tabla music. Like Bach’s fugues, this music is played forward and backward according to strictly mathematical formulas, for example, a + b + 2ab + 2cd3 + 4ab4. I admired the extraordinary mathematical skills of the tabla players, who were able to spontaneously enter a tabla session from outside and instantly play along with the other musicians. Only now do I understand why Indians are avidly sought and highly successful as computer experts around the world.

11/19

Baby Krishna

READ MORE

At a visit to the Hindu temple, a large sign outside the gate proclaimed, “ENTRANCE FOR CHRISTIANS FORBIDDEN,” so I undressed down to my briefs, pulled a white sarong around my waist, slipped a sandalwood necklace around my neck and pressed a red dot onto my forehead. After hours of parading between monkeys, elephants and exotic fragrances, I arrived in a confined grotto-like space, where the faithful could only individually file past the holiest of holies. When my turn came, I could scarcely believe my eyes: a pink naked plastic baby doll lay on a bed of straw with its legs raised, as if it were kicking, just as though this were a European Christmas nativity scene. The plastic infant stretched its plump little arms toward me, as though it were seeking help from its viewer. The only difference was the makeup: this Hindu baby’s eyes were adorned with a thick ring of black kajal. I saw two cultures battling with the same symbols for totally different perceptions of “truth.”

12/19

Talking Buddha

READ MORE

On my quest for traces of Buddhism, I found the Ajanta Cave, 100 kilometers north of Mumbai, where Buddhist monks had hewn entire rooms from the stony cliffs. Their extraordinary imagination had even enabled them to carve the furniture from the living rock. The Buddha figures too were carved from the stony matrix. Tables, chairs and figures thus became immovably part of the overall spatial sculpture. It grew clear to me here that the “dematerialized room,” which provides living space, is equally important as the “material room,” which provides protection. Emptiness and fullness should stand in balance. I try to bear this in mind in my artworks.

13/19

Alhambra

READ MORE

The Alhambra in Granada, Spain remains in my memory like a fragrance or a dream. Don Juan, the life partner of my German Aunt Gabriele, led me at sundown across the rose-scented garden of the Palacio de Generalife and through the chambers of the Alhambra. As a former coronel of the Spanish militia, he had possession of the key and he kept a watchful eye on everything that happened in the Moorish fortress. Juan Garcia explained to me that meltwater from the Sierra Nevada, flowing through narrow channels in the floors, cools and removes dust from the rooms, and that translucent silk veils separate one room from another. The people in an adjacent room look like a mirage: they dematerialize when a breeze ripples the veil. Exotic perfumes, kept in artfully carved niches at the entrances, are daubed onto one’s skin or clothes when one enters the rooms. In the paradisiacal garden of the Generalife, Juan recounted the story of gifts brought by visitors, who gave birds from the four corners of the Earth to the little Moorish prince. His father transformed the garden into a gigantic aviary by commanding servants to stretch nearly transparent gauze over the tops of the cypresses so the birds couldn’t fly away. I was sixteen years old when I heard this story and I thought to myself, “Aren’t we all in a situation similar to that in which the birds find themselves? We think we’re living in freedom, but in fact we’re not free.”

14/19

Ayers Rock

READ MORE

Following in the footsteps of the indigenous people of Australia, I arrived at Ayers Rock in the center of the continent. Before sunup, I climbed the world’s largest monolith, the holy mountain of the Aborigines. Reaching the platform atop the monolith, an infinite stillness reigned – and was suddenly shattered by powerful air pressure and a shrill shriek directly above my head. Startled nearly to death, I look toward the source of the scream and saw an eagle, close enough to reach out and touch, hovering over me with its large wings widely spread. The bird had obviously braked at the last instant and was similarly startled to discover that the prey it had intended to seize was ten times larger than it had seemed to be when viewed from a higher altitude. I used instinctively my camera as a weapon, hurling it at the eagle while holding the strap firmly in my hand. The bird evaded my projectile, turned 180° in the air and began its next assault. Again I flung the camera toward it. The attacks continued. The eagle and I fought for more than half an hour. Finally, he began to retreat: his prey’s resistance was too vigorous for him. The intensity of the beauty atop Ayers Rock was further heightened by my life-threatening battle with the eagle. I had doubly experienced nature.

15/19

Tai Shan Berg

READ MORE

While I was in Shanghai to shoot photos, I learned that once in his life, every Chinese must pay his respects to the five holy mountains of China by making a nocturnal climb. My Chinese friend Er Peng accompanied me one night on an ascent of holy Mount Taishan in Shandong Province. We began our climb at one o’clock in the morning so that we could reach the summit in time to watch the sunrise from the peak. The night was warm and humid at the foot of the mountain. I began the climb in short pants and a T-shirt, with my camera equipment strapped to my back. The path for pilgrims leads toward the summit as a series of stairs. The irregular heights of the steps, which varied by as much as fifty centimeters, were frustrating for me in the darkness. I repeatedly stubbed my toes against risers where I had expected stairs to be lower. Er laughed out loud each time I shouted “ouch”: he was accustomed to night hiking from his military service in the Chinese army. We finally reached a rest stop, where I bought a little flashlight for thirty cents. Now I could climb more quickly, but I nonetheless felt like a snail as I watched other pilgrims pass me by and continue jogging up the stairs. The weather grew colder and at precisely the point where the cold was no longer bearable, we found a little hut where olive-green felt overcoats from Chinese army surplus were available for rent. We were issued a number as though it were a coat check. Er Peng left his wristwatch as a deposit. Finally properly clad, we continued our ascent toward the summit, where we found hundreds of people perched like a colony of birds along the rocky rim of the peak, each one nearly motionless, uniformed and speaking, if at all, only in whispers. It was a meditative scene, like an archaic memory or the silhouette of a birdman slowly appearing from the darkness of the misty night. Only now did I understand that I was standing at the summit above the clouds. As though on a giant stage, the sun obeyed the command of some hidden stage manager and rose like a round, red-painted, cardboard cover through pale grey cotton wadding. All around I heard people whisper the word yume (sun). As though a great theater production had just concluded, the pilgrims silently departed from the summit. It all seemed as though nothing had happened, and suddenly the world appeared to me just as it must have looked for millions of years before human beings came into existence. In that same moment, my own existence lost its meaning.

16/19

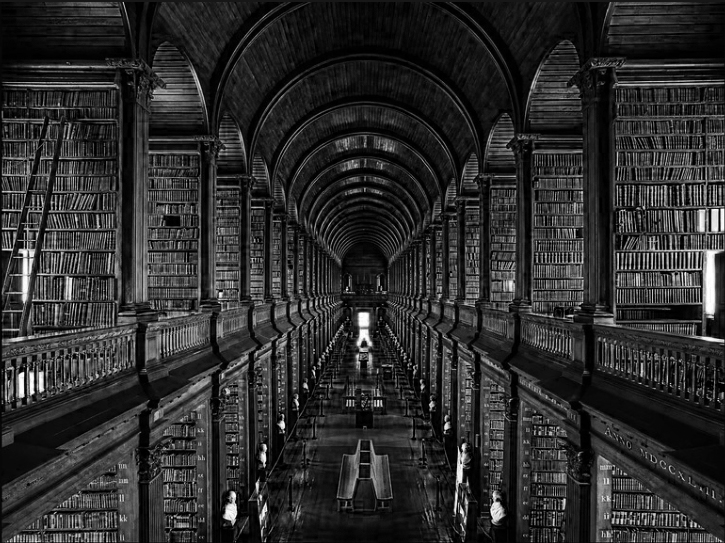

Bibliothek in Cambridge

READ MORE

During my stay in England, I visited the sacrosanct library in Cambridge, where I saw a sea of books kept in infinitely tall bookshelves. As I entering the hused hall, I thought, “How peculiar it is that despite all man’s knowledge, we still have no idea where we come from or where we’re going.” The claim that we know anything at all seemed shaky to me too, because the state of our knowledge is constantly changing.

17/19

Soulmate

READ MORE

In 2001, I met for the first time a person to whom I am connected by a spiritual kinship. Everything dematerialized in Shia’s poetry, similar to the visions in my worlds of imagery. Through her, I found my way into my own world of sounds, which engender my pictures. She made it clear to me that I have to build an artwork not as I had intended, not in voluntarily chosen monastic seclusion, but in the midst of our globalized world of art-making and the art business.